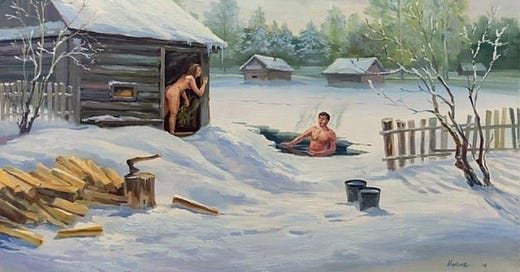

Painting by Alexander Gerasimov (1938)

Below post is an excerpt from a new book I am writing now. The working title of the book is "Understanding Russians: A guide to the Russian mentality and lifestyle."

“Idi v banyu!” (“Go to banya!”) is a mildly rude, yet socially accepted Russian idiom that translates to “Get off me!”

Banya (баня) is a Russian sibling of sauna, although sauna is also popular in Russia and often both terms are used interchangeably. In the pre-revolution Russia and throughout Soviet times, in rural areas banya used to be a place for weekly bathing. There were no daily showers and many people bathed once a week at best. Banya takes time to set up and using it daily was not an option.

Using banya as a primary way of bathing is still the case in many remote places of the country. However, nowadays in Russia modern bathing facilities have replaced banya and showers are commonly used for personal hygiene.

Banya has become a means of recreation, wellness and socializing. With reference to activities aimed at building social connections, banya is a pinnacle of social rituals of establishing close relationships in Russia.

Since banya is one of the most popular recreational activities in Russia, many, if not most, owners of private houses or dacha have banya on their premises. Banya is a separate building, not adjacent to, sometimes on a considerable distance from the house. Equipment of each banya depends on what an owner can afford. For some, it’s just a small shack with a tiny antechamber, which is used for changing and resting. Banya of the rich includes amenities like showers, toilets, separate dressing rooms, a poolroom, a spacious lounge with leather armchairs, a TV with karaoke, a kitchen and a bunch of everything else that money can buy.

The centerpiece of every banya is a wooden steam room with a wood burning heater that has natural stones laid on top. The heater can also have a built-in tank with water, which heats to be used for washing. Most of the remaining space is taken by stepped long wooden shelves, usually two, maximum three levels one above the other.

Preparation of banya starts with firing some chopped wood in the heater. More chopped wood is added, so the temperature inside steam room reaches somewhere around 90–100 degrees Celsius (194-212 Fahrenheit). The temperature level depends on personal liking; in some cases it would be as low as 60 degrees (140F) or rise well above 100 degrees (212F). When the temperature reaches the desired level, it’s time for banya ritual.

First, bathers settle in the separate space, a room adjacent to the steam room, called predbannik (предбанник). At a minimum, it usually has some hooks for clothing, a sitting arrangement and a table. Bathers bring drinks and snacks to enjoy between trips to the steam room. As for drinks, it is customary to have some light alcohol, such as beer. Some folks like it alcohol-free (healthier) options and bring kvas (квас), mineral water, mors (морс), teas and other beverages.

If a company is of mixed genders, banya can be used in turns for men and women, and you’d have to decide who goes first. More often the whole company, men and women, go to banya together. In a steam room, if banya is used for a company of the same sex, everyone would be naked, although in some households they might use swimwear. When it’s a mixed-gender banya hangout, swimwear becomes almost a must, yet with Russians, you can never be sure. As an option, for the most authentic banya experience, bathers get naked inside a steam room and dress back again leaving it. Often dressing means wrapping one’s body into something like a bedsheet.

Once inside a steam room, it is customary to sit on a shelf (the higher the shelf, the higher the temperature) for a while to get used to the heat and warm up. In contrast to dry saunas, popular in Finland, Russian banya is “wet”. To add humidity, a ladle of hot water is poured onto stones, which top the heater, making water to evaporate instantly. A wave of hot steam hits bathers. To protect head and ears (one of the most sensitive body parts) from heat, bathers use special hats made of felt.

The key of banya ritual is paritsya (париться). Russian banya uses bath whisks made of tree branches with dry leaves. The most popular are birch and oak leaves, but other tree species can be used. The bath whisk is soaked in water beforehand. A bather lays flat on the shelf, while one of his or her companions whips them with that wet bath whisk, tip to toe, front and back of the body. Well, it’s a simplistic explanation of how it works: seasoned banya users practice special techniques, so whipping brings pleasurable physical sensations and healing benefits. In public bathhouses they have professional bath attendants, skilled in using a bath whisk efficiently to the maximum satisfaction of a bather. In private banya, bathers paryat (парят) one another, and this is a term for whipping with a bath whisk.

Banya ritual continues with jumping into cold water in the nude, straight out of the steam room, for which many banya owners have a special font, inside or outside. As an alternative, it can be a jumping in a nearby open water, if it is available, or simply pouring a bucket of ice-cold water on one’s head. In winter, it is often falling into a snowbank, sometimes followed by rubbing one’s body with snow, again with the help of other fellow bathers.

Refreshed, the company return inside, wrap their bodies in bedsheets, towels or bathrobes, pour some drinks, toast and continue their leisurely conversation. The ritual is repeated for several times, until everyone gets extremely weary, when it’s very late and the only thing you can do is tumble fall into bed and drift off.

There are thousands of traditions of banya rituals, but since this is not a banya manual, I am giving you a basic (which I believe most Russians adhere to) way of using banya. Now you know what to expect if Russians invite you to their dacha, or their house, announcing that there will be banya.

Yet, banya, as a recreational activity, goes beyond bodily enjoyment. It’s a way of socializing, where building or sustaining trust relationships through personal openness becomes literally physical to a degree of being intimate. Possibly it’s the closest you can get to another person: being naked in a cramped space, touching bodies and whipping one another with those bath whisks. In saying this I am not suggesting even a remote hint of eroticism. It’s the utmost way of human openness and closeness without stepping over a threshold of sexual intimacy. Together with emotional affinity, it’s a way of achieving and securing more closeness to someone. That said, if you are invited to a Russian banya, the unspoken message that follows along with an invitation is: we trust you, we like you, we want to connect, to know you closer. Banya is an act of communion that works through giving up personal privacy. Being in the nude, perhaps under the influence of alcohol, engages you in more honest, direct and open conversations, which is the basis for building trust relationships with Russians.

For large city habitants, public banyas are available, they come in various levels of service and consequently, different prices. Private banya (sauna) can be rented too, and in most Russian cities you’ll find multiple options to choose from.

Often banya is a way for close friends to spend their time together. It can be a company of men or women friends hanging out in someone’s private or a public banya. In the iconic Soviet movie “Ironiya Sud’by Ili S Legkim Parom, “The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath!” (Mosfilm, 1975, Directed by Eldar Ryazanov)” a public banya visit of a company of friends becomes a key part of the plot. You can watch the movie on YouTube with English subtitles.

Some businesses have corporate banya or sauna for their employees to use. It can happen that discussions on important business subjects go well after business hours. To combine business and leisure, meetings continue in banya or sauna, where, in a relaxed atmosphere of openness and trust, decisions and agreements are made, and business deals sealed.

On the outside, banya seems to be a part of Russian lifestyle, a popular recreational activity and a way to spend leisure time. Looking deeper, banya reveals itself as means for building closer connections, be it a business or personal life. In certain western societies, dropping hints on close relationships with someone, people say: “I play golf (or any other popular sport or activity) with such and such.” In Russia people say: “I go to banya with such and such.”

When banya is over, bathers say one another: “S legkim parom.” In a very rough translation that means: “[Congratulations] with light steam!” After banya you feel like a newborn and congratulations are for that lightness you sense in your body and mind, for getting rid of all the toxins, physical and emotional.

Are you ready to experience Russian banya?

Some of my best memories are from the steaming and washing sessions at my childhood banya. I can’t really experience that in the U.S. anymore. Even though there’s a Russian spa where I live, it’s not the same as the one at our dacha.