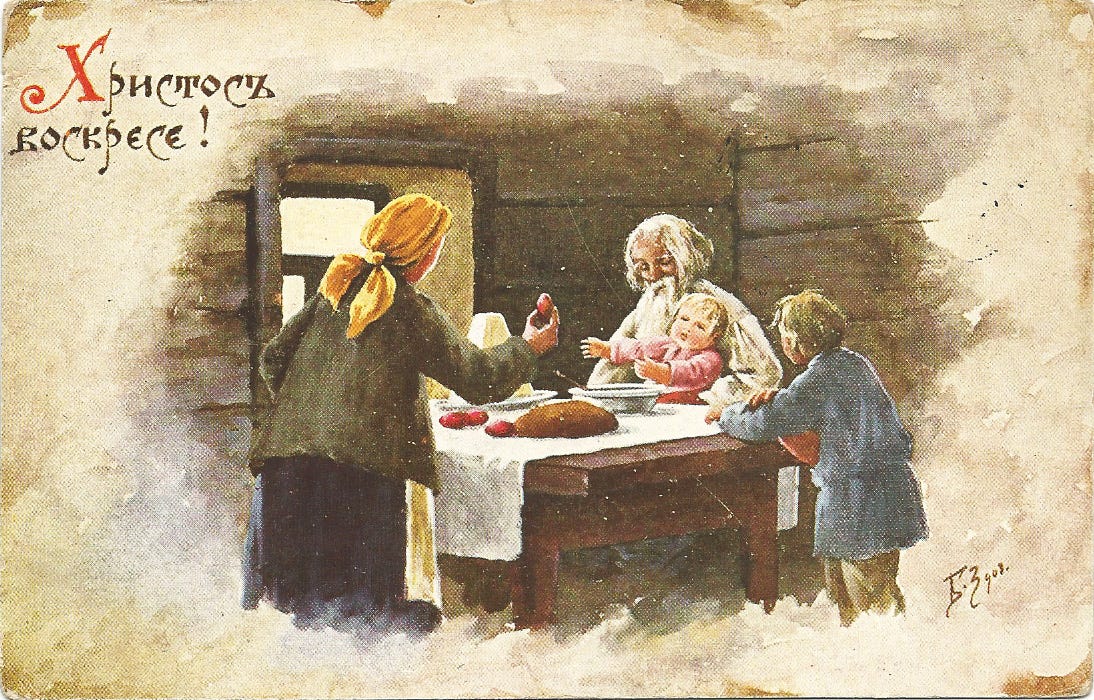

In the picture: A pre-revolution Easter postcard.

For a significant part of known country’s history, Russia had Orthodoxy as a primary religion, which was not only widespread, it was a backbone of the Russian state, lifestyle, and traditions. As we know, the Soviet system from its very inception aimed at destroying religions and ridding the lifestyle of Soviet people of anything Orthodox. They did achieve the eradication of the Church, but did not destroy it completely. Throughout Soviet rule, the Orthodox Church kept its wisdom and traditions, passing it on from generation to generation of clergy and congregations, which still quietly dwelled in a few small convents and parishes scattered across the country.

In light of Perestroika in the late 80s, religions came out of the closet and, having official support, started to grow and revive old traditions. However, the outreach of Orthodoxy never achieved what it used to be before the mutiny of 1917. Following all the rules of the Church was not for every ex-Soviet citizen, as Orthodox doctrines are extremely demanding, complicated, and require lots of studying, deliberate practice, and ultimately, one’s dedication and undivided faith. Still, there is a huge population of believers, faithful members of the Church, who follow all the traditions of Orthodoxy (and those traditions are fascinating).

Yet, the minds and lifestyles of ordinary Soviet citizens, atheists, communists, and alike, had a place for deeply rooted tradition, which they carried throughout decades of Soviet rule. Remembering Easter as a greatest of holidays that existed in pre-revolution Russia, it was observed in Soviet times, unofficially, privately, behind closed doors, following minimal rituals and customs. However, not being sustained with spiritual nourishment and practice, over the decades, for the general public, Easter has lost its scriptural significance and has turned into a common, generic festivity.

Nowadays, both celebrate Easter, active devotees of Christianity, and people who have very little to do with any organized Christian religion. Easter in Russia is huge. On the outside, for an unaware beholder, it makes an impression that the majority of the population are deeply involved with religion. That is absolutely not the case. Observing Easter en masse, the general Russian population pursues togetherness, following tradition, conformity, and social approval, but that does not equate to seeking Christ. Most of those celebrating Easter have never opened a Bible in their life and cannot explain what Easter is.

The Church has its own way of proceeding with Easter festivities. There will be many special services, an overnight service on the night between Saturday and Sunday of Easter, a sacred procession. In this publication, I won’t write about the Orthodox traditions of preparing and celebrating Easter. For those interested, the internet provides resources to guide you on how Orthodox Christians proceed with observing Easter. This piece will explain how regular, average Russians, who are not adherents of the Russian Orthodox Church, celebrate Easter, even if they are not really aware of what it is. For people not actively participating in church life, Easter is not what it is for a true believer.

Stepping outside the church, what you are seeing as a traditional way of celebrating Easter on a social level is a number of memorial artifacts that were left after decades of the Church in obscurity during Soviet times. For the general public, Easter is a holiday with its own meaning attached to it. It's a mere tradition that was kept throughout history, but the origins of which have been forgotten. I write specifically about Easter because, even being detached from the church, its tradition, and cultural significance, Easter somehow made it through the decades of Soviet atheism. Other Christian holidays of importance, such as Christmas, are not celebrated practically at all, unless, again, an individual is going to church regularly, reads scripture, and meticulously follows church traditions.

Easter is preceded with a Great Lent, and even those who never go to church get involved in what seems to be a purely religious thing. Restaurants and eateries of all calibers roll out special Lent positions in their menus. Food manufacturers mark some of their products "постное" as being compliant with the Lent requirements. You’ll hear from folks around you, friends, colleagues, and relatives that they are on Lent, refusing to eat certain types of food. The food that is banned from consuming during Lent is called “скоромная еда,” and for the most part, includes products of animal origin. Why fast if one is not an active member of the church? Well, perhaps they see Lent as a good reason for the spring cleaning of their bodies, shedding some extra weight for the spring and summer. Many just want to be trendy because to fast is cool and everyone around is doing it. It very well may be that few folks believe food restrictions bring goodness on a supernatural level, only they will never admit it publicly.

Another tradition of Easter is coloring eggs and baking kulich or paskha. Kulich is a ritual bread, cylindrical-shaped pastry, with a sweet taste. Its top is rounded and has a white sugar glazing. Traditionally, kulich was baked in each household, but nowadays, in stores, you’ll find a wide choice of factory-made kulich, so people simply buy one. There are traditional recipes for making paskha, which is an alternative to kulich, also an Easter ritual pastry, but of a different kind, made of cottage cheese, not using flour. Making paskha is time-consuming, and few people bother to make it at home. It has a white, truncated pyramidal shape, with “XB” capitals embossed on sides, the first letters of “Christ has risen” in an ancient Russian language. In families of true believers, many take time to bake their own kulich or paskha.

Weeks before Easter, grocery stores start selling supplies for coloring and decorating eggs. Colored eggs are one of the symbols of Russian Easter. I bet no one knows why, but still, the tradition tells to color eggs, and many, if not most, families prepare them for Easter. Eating those colored eggs must be preceded by a ritual. Two folks take colored Easter eggs, one for each, and crash those egg's sharp ends against one another to make the shell crack, saying “Христос Воскресе!”, which is “Christ has risen!” A ritual reply to this is: “Воистину Воскресе!”, which translates as “Truly risen!” This ritual greeting people will also say meeting on the day of Easter.

On Easter Day, you'll see long lines at the churches of those who have come to bless their eggs and kulich. The priest will come outside after the Liturgy, spraying water onto the kulich and eggs, as well as the congregation. The atmosphere is so festive, you want to be a part of it even if you have nothing to do with Orthodoxy at all.

On the day of Easter, Russians go to cemeteries to take care of the graves of deceased relatives. Most Russian graves are individually fenced and have a tall tombstone with names, dates of birth and death, and a picture of the person buried. On Easter Day, the grave gets cleaned, flowers planted, after which relatives have some alcohol on a gravesite, and food for remembrance of those passed away. Some of the alcohol is spilled on the grave, and some food (especially sweets) is left, for “feeding” those not with us any longer. As far as I know, this tradition of feeding the dead comes from the pagan part of Russian history (over 1000 years back!) and the Orthodox Church doesn't approve of it. According to the Orthodox Church, Easter is not a proper day for visiting cemeteries either. There are special days of remembrance that are established by the Church for that very thing. Yet, people believe otherwise, and you’ll see hordes of citizens heading to cemeteries on Easter. Knowing that, local authorities often organize extra bus routes to the cemeteries and extra amenities for visitors.

You’ll see cities decorated with Easter themes, and public events taking place on the streets. Those are not church-organized events, but means of mass entertainment. Like any other festivity, Easter works as a good occasion to invite family and friends for a home gathering. In Orthodox tradition, Easter is an official end of Lent, when some food indulgences are allowed. Modern Russian culture takes advantage of the termination of Lent in full: many families make feasts for Easter, because after all, it’s a grand holiday, and why not rejoice and have a good time with dear ones?

Final thought. I sense that deep inside, maybe secretly, everyone who is celebrating Easter, not being a faithful member of Orthodoxy, expects the grace that all the Orthodox tradition is believed to bring. They do anticipate goodness and a blessing, even if they never go to church and never studied scripture. What it tells me is that on the subconscious level, spirituality is an irrevocable part of the Russian culture code, which manifests in different ways, be it mere superstitions, being involved with one of the major religions, or blindly following rituals, even if they have no idea of their meaning and have only a remote resemblance to traditions of their ancestors. Even the decades of communism with its belligerent atheism couldn't erase that spiritual seed from the core beliefs and values of Russians.

Thank you. What a wonderful way for the country to feel as one.